The batshit evolution of SARS-CoV-2

Are there laws of evolution that are unique to SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses? Or were sequences invented to conceal its artificial origin? This is trivially easy with a system based on trust.

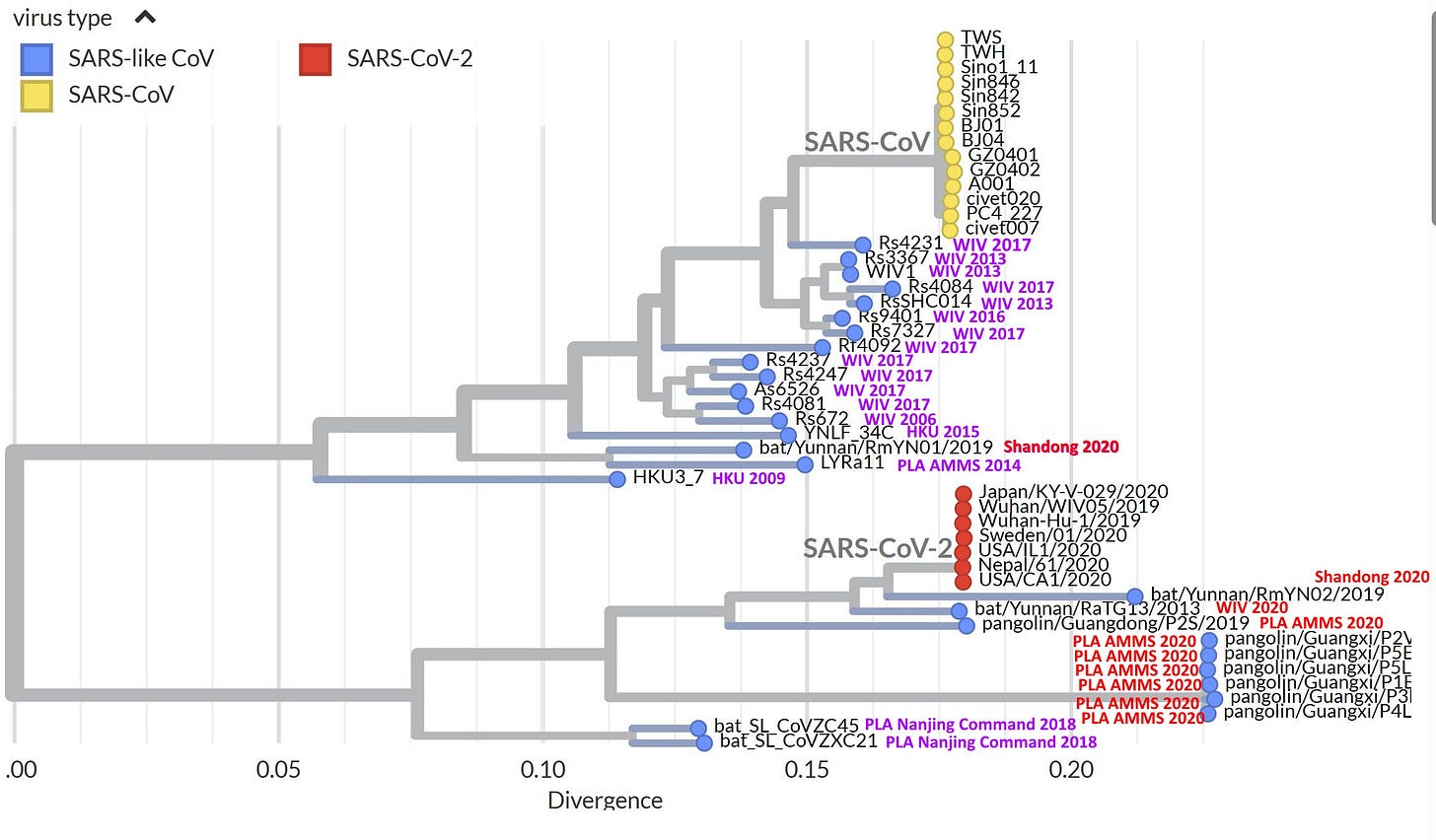

In September 2021, Institut Pasteur announced the discovery of 5 bat coronaviruses they named the Banal (for Bat-anal) viruses. One of these - Banal-52 - was proclaimed the closest known virus to SARS-CoV-2, supplanting WIV’s RaTG13. Up until the announcement of the Banals, the reigning theory of SARS-CoV-2’s evolution was that a bat virus very similar to RaTG13 had recombined with and acquired the receptor binding domain (RBD) from a pangolin coronavirus (PCoV).

Even some natural origin proponents were unconvinced by this hypothesis. Pangolins are solitary by habit, not an ideal host environment for a virus to evolve respiratory transmission. Recombination also requires that the bat and pangolin virus must infect the same host. A survey of 340 pangolins by EcoHealth found no evidence of a coronavirus, while another paper showed they weren’t for sale at Huanan market.

Lab-leakers were justifiably suspicious of both RaTG13 and the PCoVs. RaTG13 was sequenced by WIV perhaps as early as 2017, but they kept it secret. Some partial sequences were uploaded to GenBank in July, 2018 but they were hidden from public view, and the all-important Spike gene was missing. Even after the outbreak it was weeks before WIV admitted they had the closest zoonotic sequence by far to the novel coronavirus. It was shifty behavior from Shi Zhengli, already under suspicion due to the location of the outbreak.

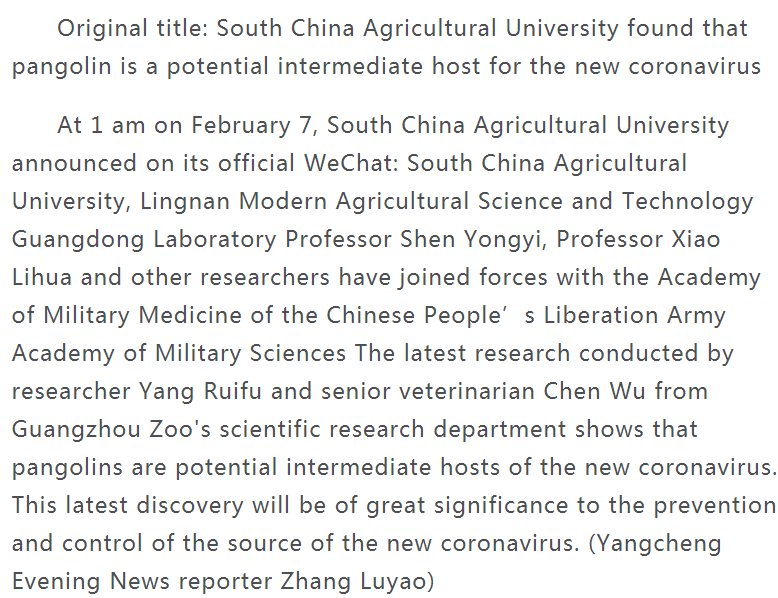

On September 20th, 2019, two scientists from Guangdong Institute of Applied Biological Resources (GIABR) set up a GenBank repository for pangolin metagenomes, which included reads from a novel coronavirus. They wrote a paper in a low-profile journal announcing this discovery, but didn’t upload the data until four months later (at the same time WIV made RaTG13 public). The GIABR scientists hadn’t sampled any pangolins themselves. The data was given to them by a 3rd author, Chen Wu, a vet from Guangzhou Zoo. Chen later provided this same data to other institutions who claimed their own discoveries. It was unclear for a long time who was responsible for the sampling, and whether there were multiple virus discoveries, or just one.

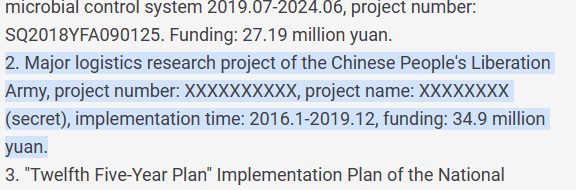

Behind the scenes it was apparent that the PLA’s Academy of Military Medical Science (AMMS) was distributing pangolin samples and data to select civilian research groups. It was later revealed that AMMS had been experimenting with pangolin coronaviruses as far back as 2017. AMMS scientist, Tong Yi-gang, was working on a secret military research project when his group claimed to have first isolated a PCoV.

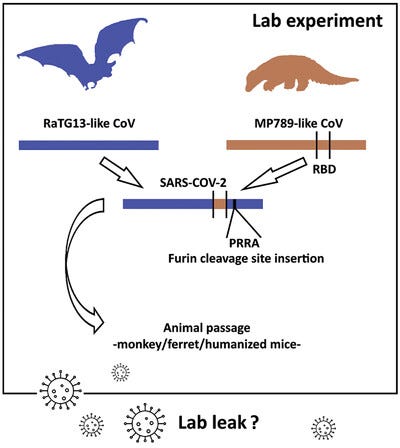

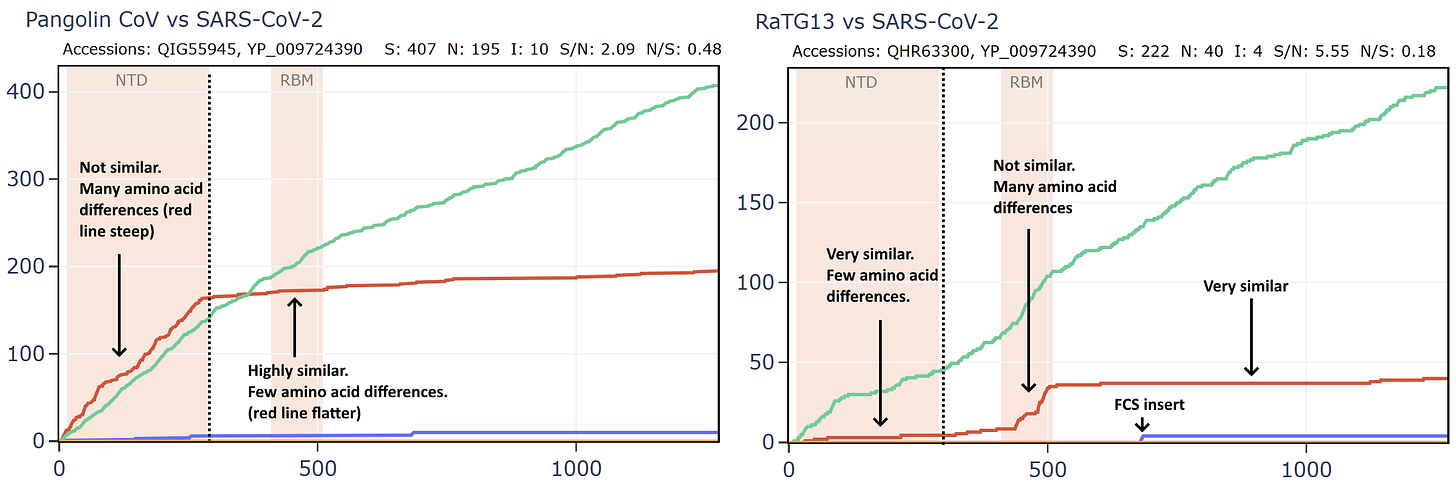

Although the PCoV genomes are overall quite distant from SARS-CoV-2, one of them (the Guangdong or GD PCoV) has an RBD which is remarkably similar. To complement this RaTG13 has a genome that is overall very similar to SARS-CoV-2, but the RBD is different. A recombinant of the two taking the backbone of RaTG13, and substituting the RBD of GD PCoV, is indeed very close to SARS-CoV-2. But lab-leakers pointed out that even if RaTG13 and PCoVs were themselves natural, this “recombination” could have happened in a lab. It would be of similar design that WIV and others (e.g. Ralph Baric) had already used several times for artificial chimeras - there are even patents covering it.

However, neither the PCoVs nor RaTG13 had the furin cleavage site (FCS) insert, and this remained a focal point of suspicions. At the same time the RaTG13 and the PCoVs were published, British zoologist Alice Hughes was contacted by Shandong University’s Shi Weifeng. Hughes had been working in Yunnan collecting samples from bats. In 2018 she was approached by Shi Weifeng to send his team bat fecal samples, and they would sequence them. In January 2020, he informed her that his group had sequenced SARS-like coronaviruses from samples she had sent. One of those viruses - RmYN02 - doesn’t quite have an FCS, but has a sequence suggestive of a possible evolutionary step to (or from) one. Although a civilian, Shi Weifeng and his team have collaborated often with AMMS over the years. He is particularly close to Tong Yigang, with whom he jointly led China’s mission to Sierra Leone during the Ebola epidemic of 2014. Since Alice Hughes had no involvement in the sequencing, she has no way to be sure such a virus came from samples she collected.

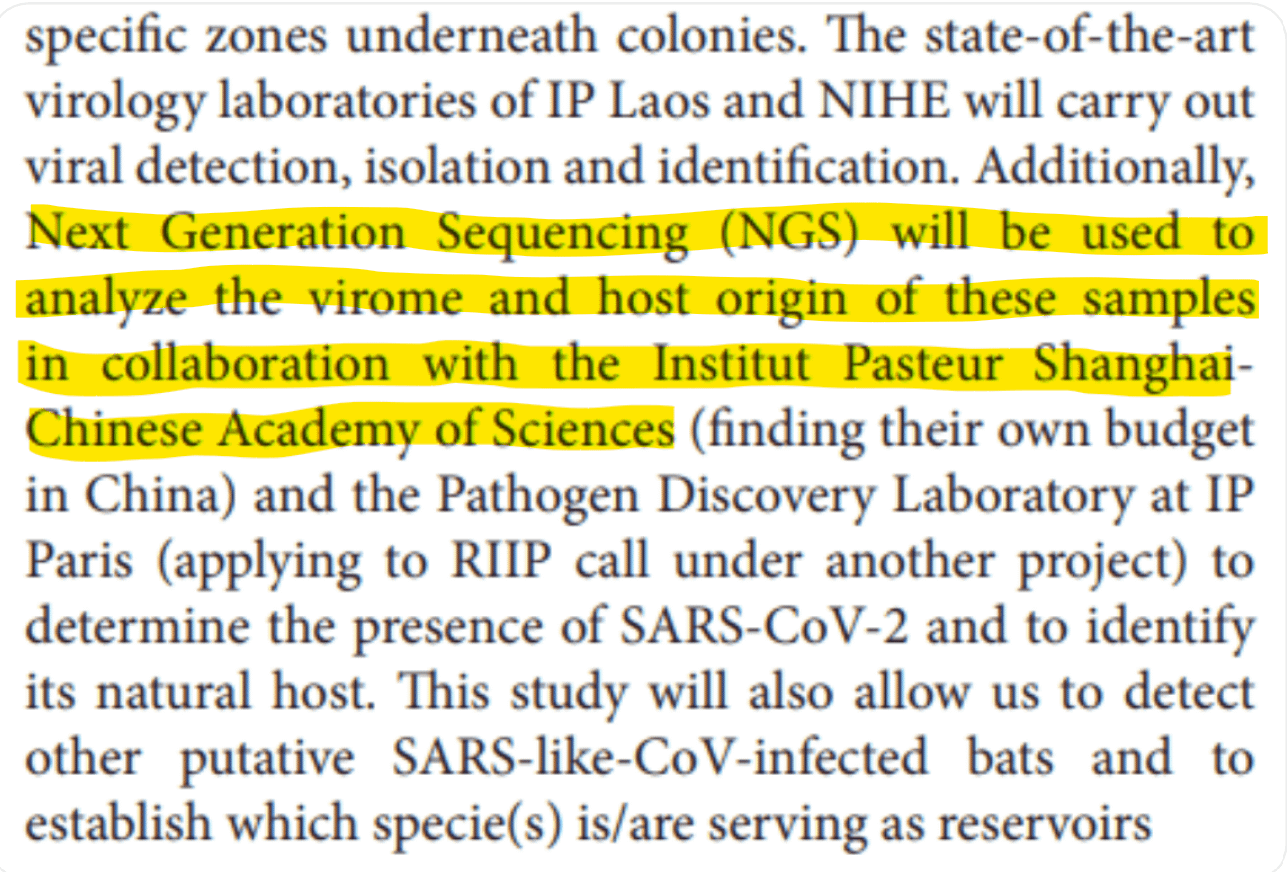

In July 2020, with the artificial origin controversy not subsiding, Institut Pasteur launched an expedition to sample bat caves in Laos. Curiously, they had only recently sampled these caves on a project funded by the US Department of Defense. On that occasion they collected over 500 samples from bats - but hadn’t sequenced any of them. These sat untouched in a freezer in Paris while they embarked on a new field trip. Why would they do this? Possibly because this time they intended to involve Institut Pasteur Shanghai (IPS) in sequencing the samples. IPS is a joint venture with China’s Academy of Sciences (WIV’s parent entity) and is staffed mostly by Chinese scientists. It may have been unacceptable to the US DoD to share samples with an institution so close to WIV.

The Banal sequences weren’t published for another 15 months after the samples were collected. In the meantime, other related sequences had been announced, but none were any closer to SARS-CoV-2, and all lacked the RBD and FCS.

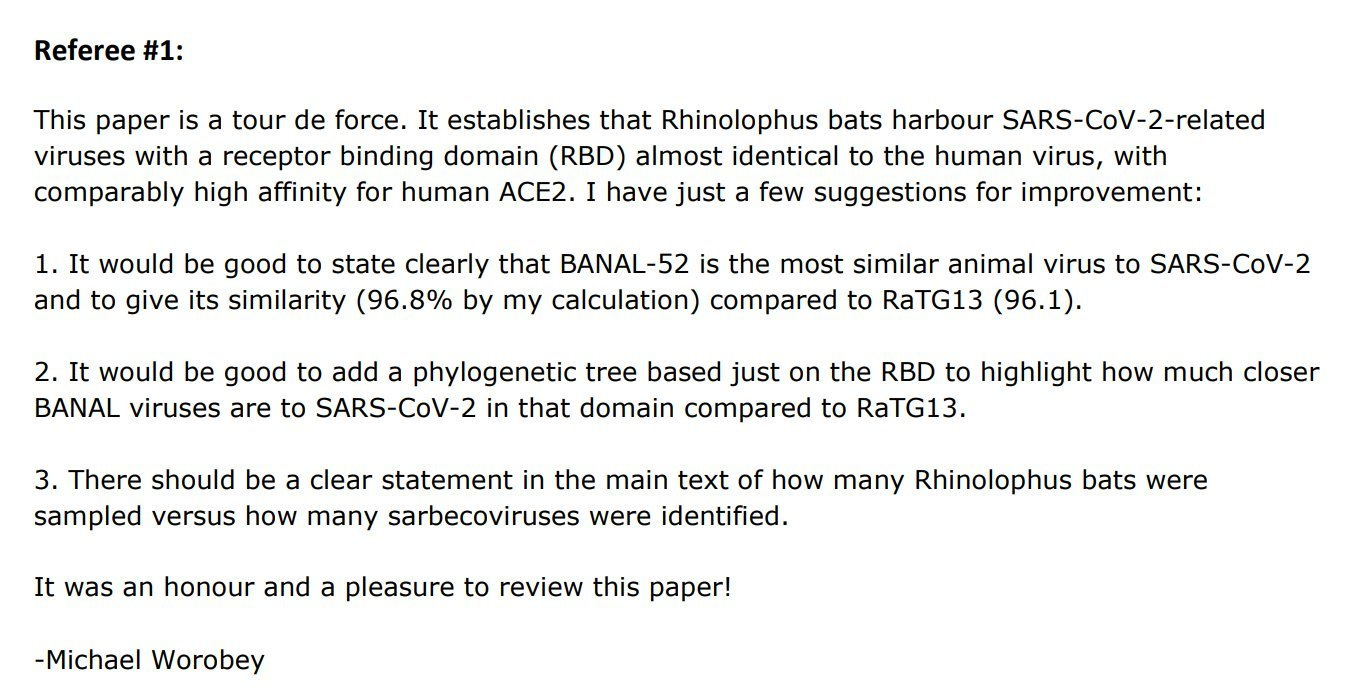

When the Banals were announced, they were hailed by some as definitive proof SARS-CoV-2 was natural. Surprisingly, they weren’t rejected by lab-leakers either. Partly because they added to the growing pile of viruses that were related, but did not have an FCS. This might be interpreted as not diminishing, and perhaps even increasing the likelihood of a lab origin. The senior author of the Banal paper, Marc Eloit, went on the record saying he thinks an artificial origin is possible and should be investigated. Such public statements ingratiated him to lab-leakers.

The Banals don’t conflict with a simple “experiment gone wrong” scenario, in which an FCS was artificially inserted into an otherwise natural bat virus. But they do suggest many of its unusual features critical for transmissibility, pathogenicity and tropism are natural - including the RBD, which seemed already well-adapted to humans. Starting from a precursor similar to Banal-52, far less engineering is needed, making it unlikely SARS-CoV-2 was deliberately and extensively engineered for human infectivity and transmission.

Another implication of the Banal discovery is that the earlier sequences (PCoVs and RmYN02) that could have aroused suspicions of a military plot to misattribute an unnatural origin, are more likely genuine. In a remarkable stroke of luck (for the AMMS) the 5 viruses found in a single cave not only support the natural evolution of SARS-CoV-2, two of them share important features of RmYN02, and two are similar to the PCoVs.

More dangerously, the Banals support WIV’s claim that SARS-like coronaviruses evolve by an apparently unique mechanism based on recombination. This differs from a conventional understanding of recombination in that viruses exchange functional domains with one another as if they were discrete components or modules (WIV has called these genetic “building blocks”). This mode of evolution has so far only been observed in this viral family, in which it happens that WIV, AMMS and associated Chinese state institutions have published the vast majority of sequences.

If WIV’s proposed novel mechanism of evolution gains widespread acceptance among scientists, it makes it easy for future bioweapons to be misattributed as natural. It is crucial that such extraordinary claims be subjected to proper scientific scrutiny and debate, but this has not happened. Because to challenge it, is to make an implicit accusation of fraud. While the earlier “discoveries” from Chinese institutions drew limited attention from skeptics, few have questioned the Banals.

No Pressure Evolution

Banal-52 has both the SARS-CoV-2-like backbone and RBD making the need for the recombination of a pangolin and bat virus redundant. It challenges the conventional understanding of evolution in other ways.

Why would an RBD that enables efficient respiratory transmission in humans evolve in an enteric horseshoe bat virus? Why would a nearly identical spike work so well in what are physiologically very different species? Some claim that the FCS confers this capability. But it isn’t the FCS alone. The FCS helps present the RBD to the receptor, but the RBD needs a complementary structure and contact residues to form strong bonds with the receptor. An RBD would be expected to evolve a different form in adapting to human or pangolin airways vs it’s ancestral environment in a horseshoe bat’s gut.

It makes little sense intuitively, but there is a precedent: SARS-1, its civet variant, and the SARS-like bat viruses WIV claimed to have discovered a decade later. Unfortunately, this episode has also had little scientific scrutiny or debate outside a close-knit circle. I’ve recently shown it appears to be based on fraud.

Unfortunately, there’s been little interest in revisiting SARS-1, which was twenty years ago and had far less global impact. Distinctions can be made between SARS-1 and 2. It isn’t strictly necessary to show SARS-1 is unnatural for SARS-CoV-2 to be, so many lab-leakers prefer to assume it is natural. But it should raise eyebrows that the same people and institutions are proposing a very similar origin narrative on the basis of that dubious precedent. There is much to be learned from this not-so-distant history.

Measuring evolutionary pressure

This section is a simplified background for readers unfamiliar with the concept of evolutionary pressure and how it can be measured (skip ahead otherwise).

Consider a virus that infects two bats, which then become isolated from each other as one bat migrates to join another colony. The strains then start to diverge from each other, as they evolve through different mutations. Mutations happen more-or-less randomly - they can be caused by chemical reaction, or unpredictable events like cosmic rays. Most mutations don’t propagate, but occasionally they do. They may even become dominant in the strain circulating in the colony - particularly if the improve the virus’ fitness in some way. A count of the total mutations between the two strains provides an approximation of the amount of time since they split from a common ancestor.

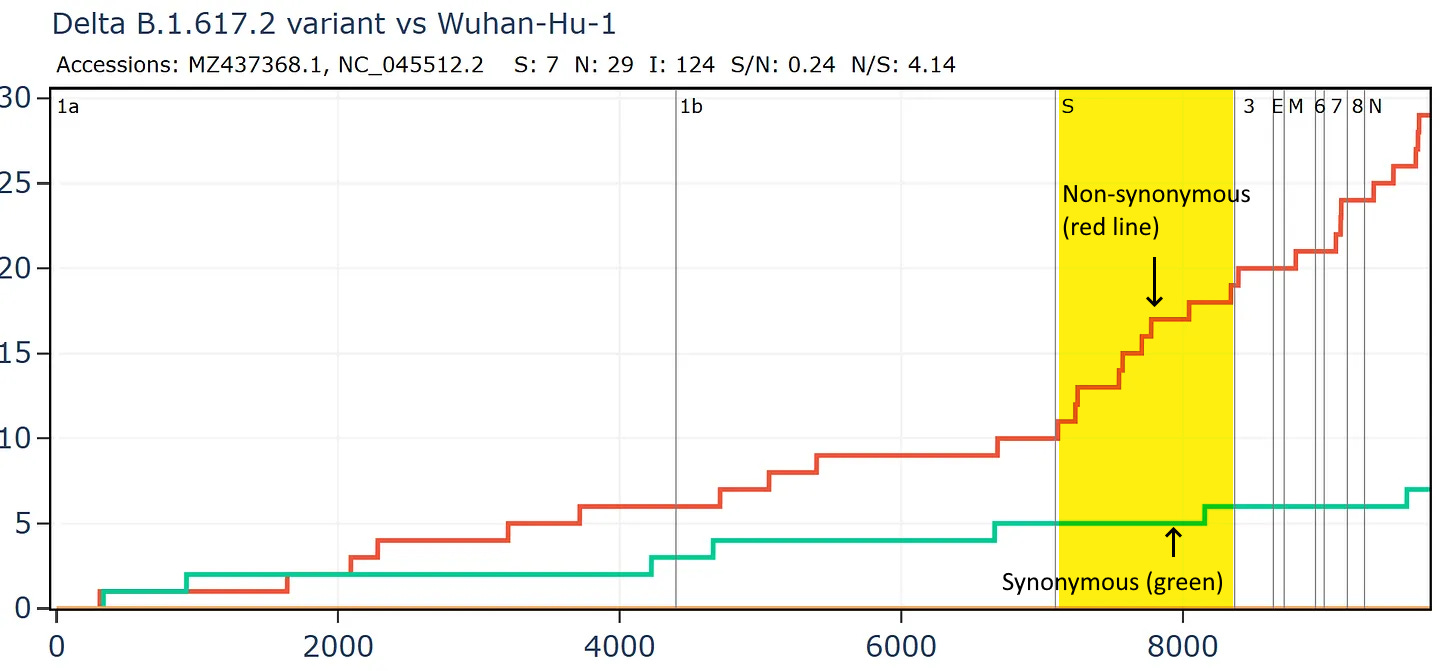

There are two types of mutations. Synonymous (S) or silent mutations don’t change the amino acid coded. Non-synonymous (N) mutations cause an amino acid change, so change the protein structure and possibly impact some viral functional. Generally synonymous mutations don’t greatly affect a virus’ chances of surviving and replicating, while non-synonymous mutations often do.

Ratios of the two types of mutations - synonymous to non-synonymous (or vice versa) - can tell us about the evolutionary pressures faced. If a virus has spent millennia evolving in a single host species, it should already be highly adapted, it doesn’t need to change to be able infect other members of the species- in fact such changes often reduce its fitness. In this scenario, non-synonymous (amino acid changes) are disfavored, and synonymous mutations propagate more frequently. The ratio of Synonymous (S)/ Non-synonymous (N) is >1 and the virus is said to be under negative (or purifying) selection pressure. Nonetheless there will always some amino acid changes that are beneficial, the virus is never perfectly adapted.

In a scenario where a virus has jumped into a new species (e.g. from a bat into a human or pangolin) the virus needs to adapt rapidly to its new host environment. Cellular receptors are different, body temperature is different, the immune system reacts differently, tissues and organs are arranged differently, pH is different. Not adapting is not an option. In this scenario we should expect non-synonymous mutations to be favored over synonymous. The ratio S/N is expected to be <1 and the virus is under positive selection pressure.

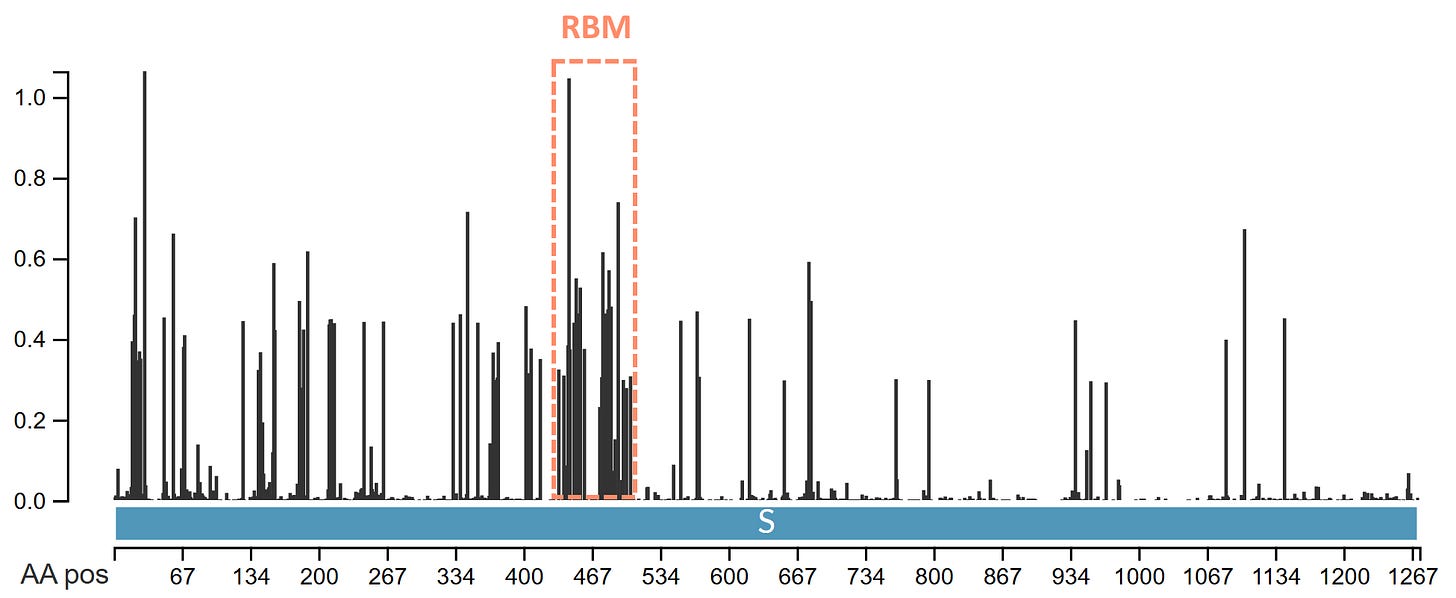

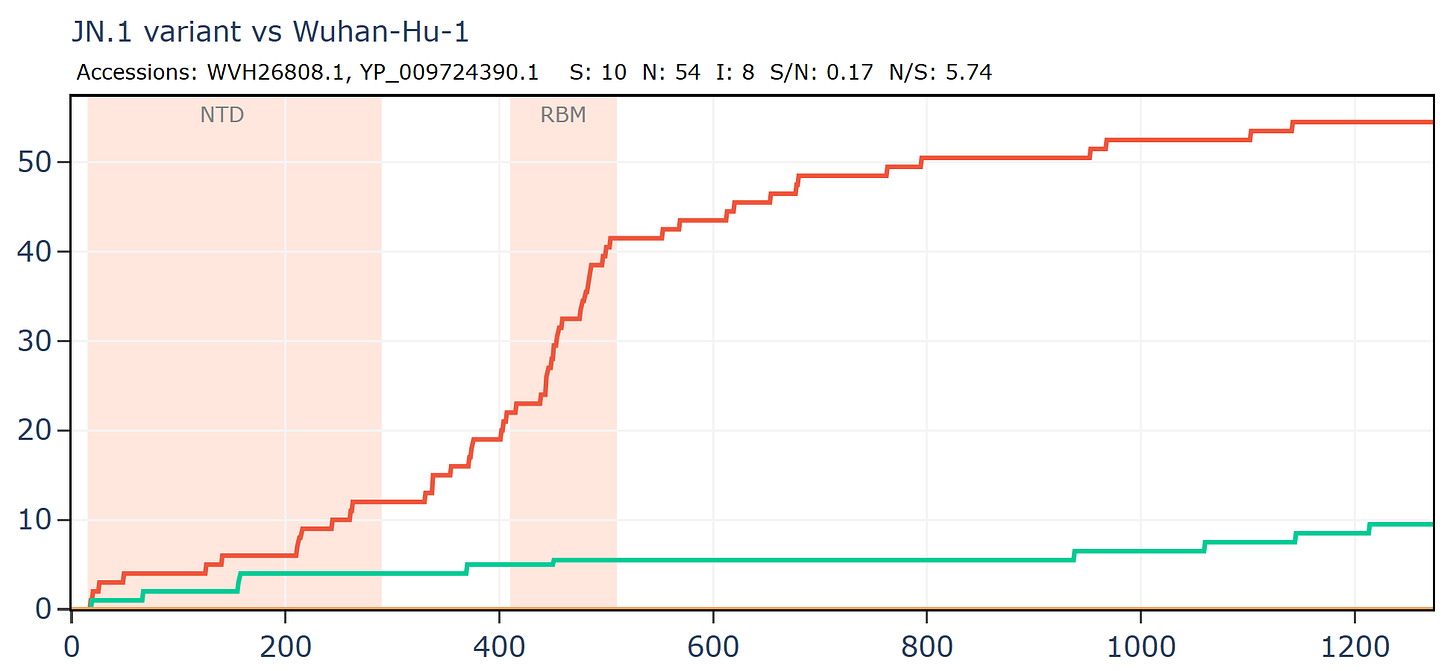

There is an additional selection pressure even on viruses that have been evolving in the same host species for millennia. It comes from the host immune system which tries to recognize the virus and generate antibodies to disable it. The virus has to change the sequence of the regions most exposed to the immune system more frequently to evade recognition. These regions are the receptor binding motif or RBM (the part of the RBD that is exposed on the surface), and the NTD, which together comprise the tip of the spike. We should always expect these regions to undergo some non-synonymous mutations over time, regardless of how well-adapted the virus is.

Observations

We can see that in human SARS-CoV-2 variants the RBM is indeed the most variable region and some surface loops in the NTD are also hyper-variable.

SARS-CoV-2 variants have very few synonymous mutations in the Spike, perhaps fewer than might be expected. The combined pressure from adaptation to humans and immunity is very strong. Comparing a Delta variant sequence to the first Wuhan sequence there are over 4 non-synonymous mutations for each synonymous, and in the spike gene the ratio is 10:1. The ratio is likely also affected by unnatural immune pressures from vaccines and monoclonal antibodies. We should keep an open mind to the possibility some variants are also genetically engineered and deliberately introduced but that is for a separate post.

Comparing just the Spike gene of a recently circulating variant JN.1 to the first Wuhan sequence, demonstrates that the RBM is usually one of the most variable regions. Here there the ratio is 19N to 1S in the RBM. Again, part of this is likely the result of unnatural pressures from antibodies induced by vaccines, forcing the virus to adapt or go extinct.

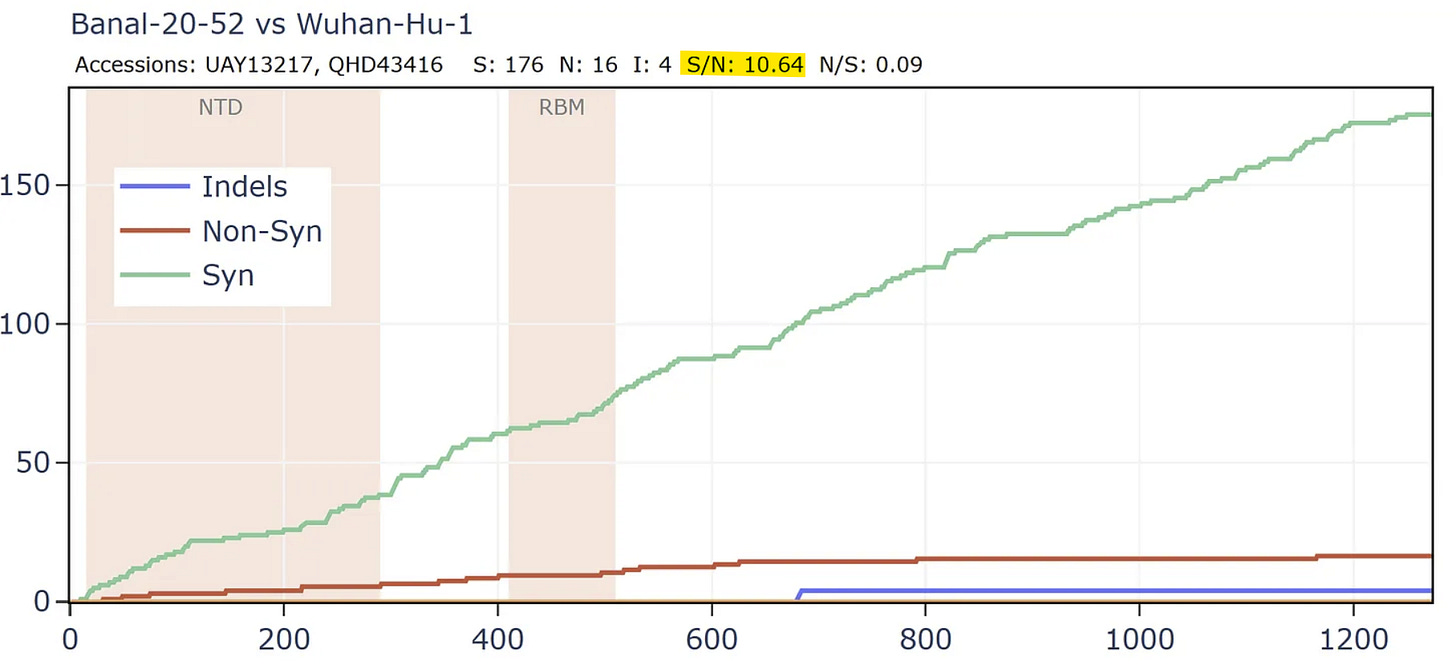

But comparing the spike of bat virus Banal-52 to the original Wuhan human sequence, the situation is reversed. In this case there are 9 times as many synonymous mutations to non-synonymous in the spike. The virus appears to have been under very little pressure to adapt to the new host. In fact, the S/N ratio of 9 is extremely high, even for a pair of well-adapted viruses evolving in the same species of bats. I have looked at many families of bat viruses and found a ratio of between 0.6 and 5 seems to be the range of normality. Many more comparisons are in my pre-print.

How can this be explained? Perhaps the virus was very well adapted to a species of bat and evolved for a long time under negative selection in Laos. It then infected a human almost immediately before the Wuhan sample was taken, giving it little time to adapt. But this doesn’t fit the circumstances of the outbreak well, and the S:N ratio is still too extreme.

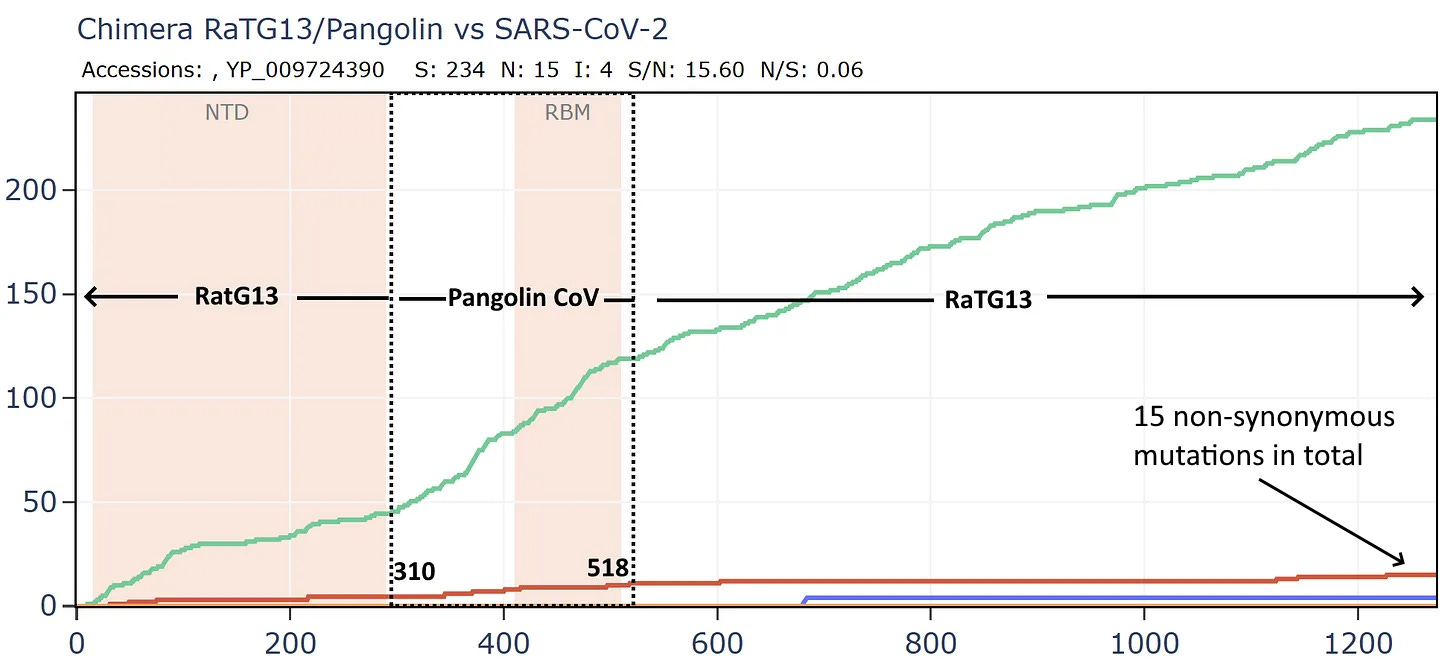

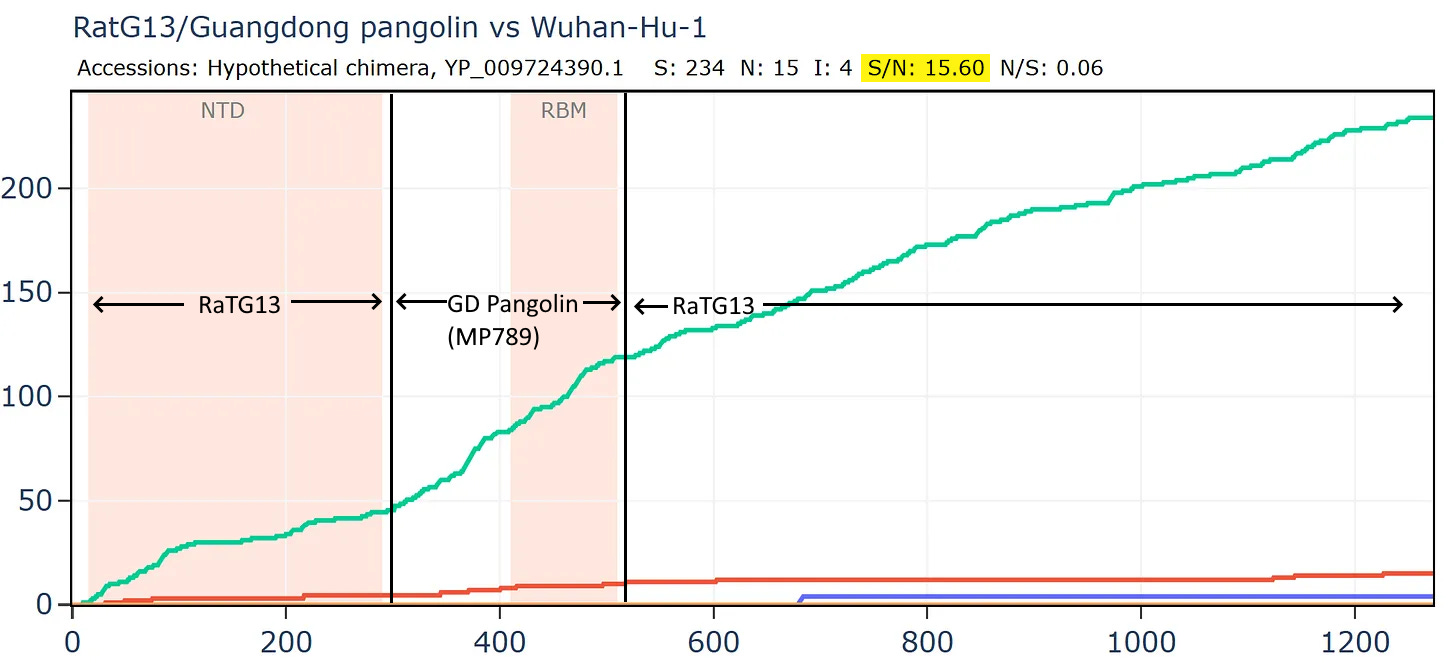

What if we created a hypothetical sequence consisting of the RBD of the GD PCoV, embedded in RaTG13, as according to the original recombination hypothesis? This means simply taking the first 310 amino acids of the RaTG13 sequence (unchanged) then from 310 to 518 of the PCoV, then from 518 to the end of RaTG13.

Curiously, that sequence is even closer to SARS-CoV-2 in amino acids and the S/N ratio is even higher with almost 16 synonymous mutations to each non-synonymous. This is strange because there are 3 different species involved, why is there so little evidence of evolutionary pressure to adapt?

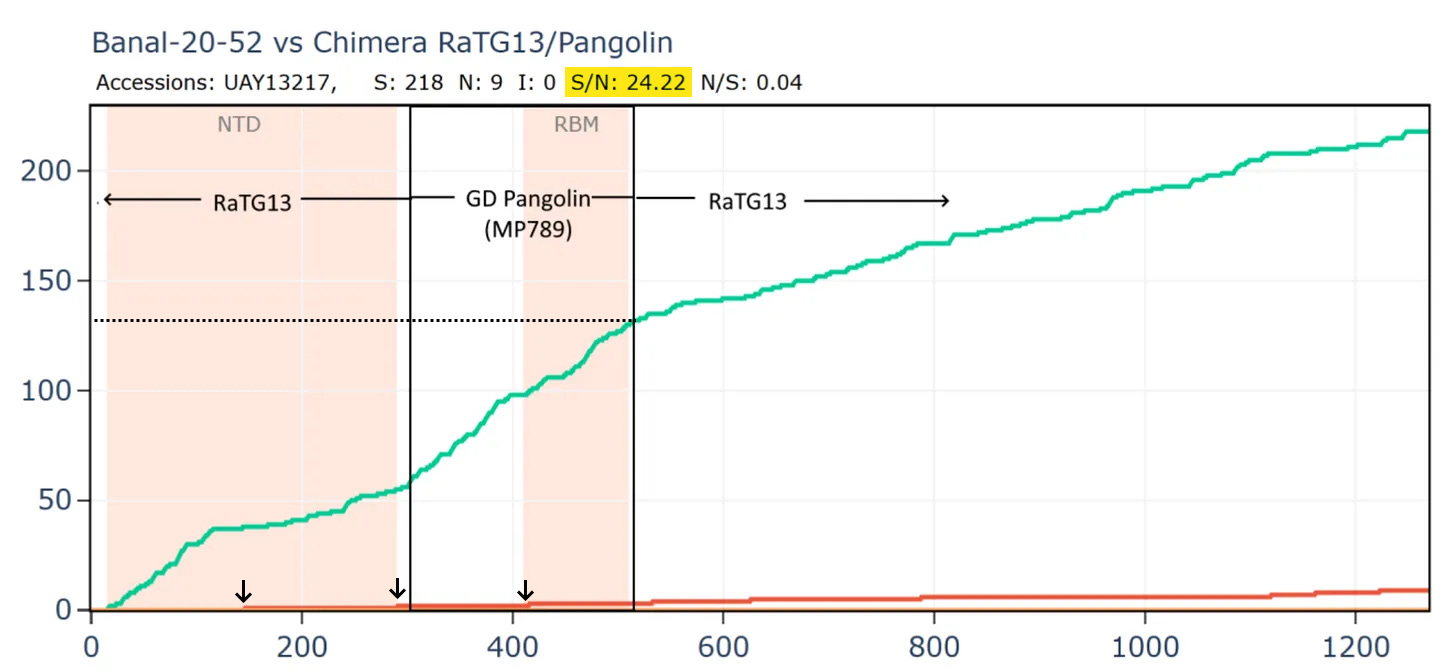

Most bizarrely - if we compare Banal-52 to this hypothetical recombinant, it is closest of - with just 9 amino acid differences. And there are over 24 synonymous mutations for each non-synonymous - this is an absurd number.

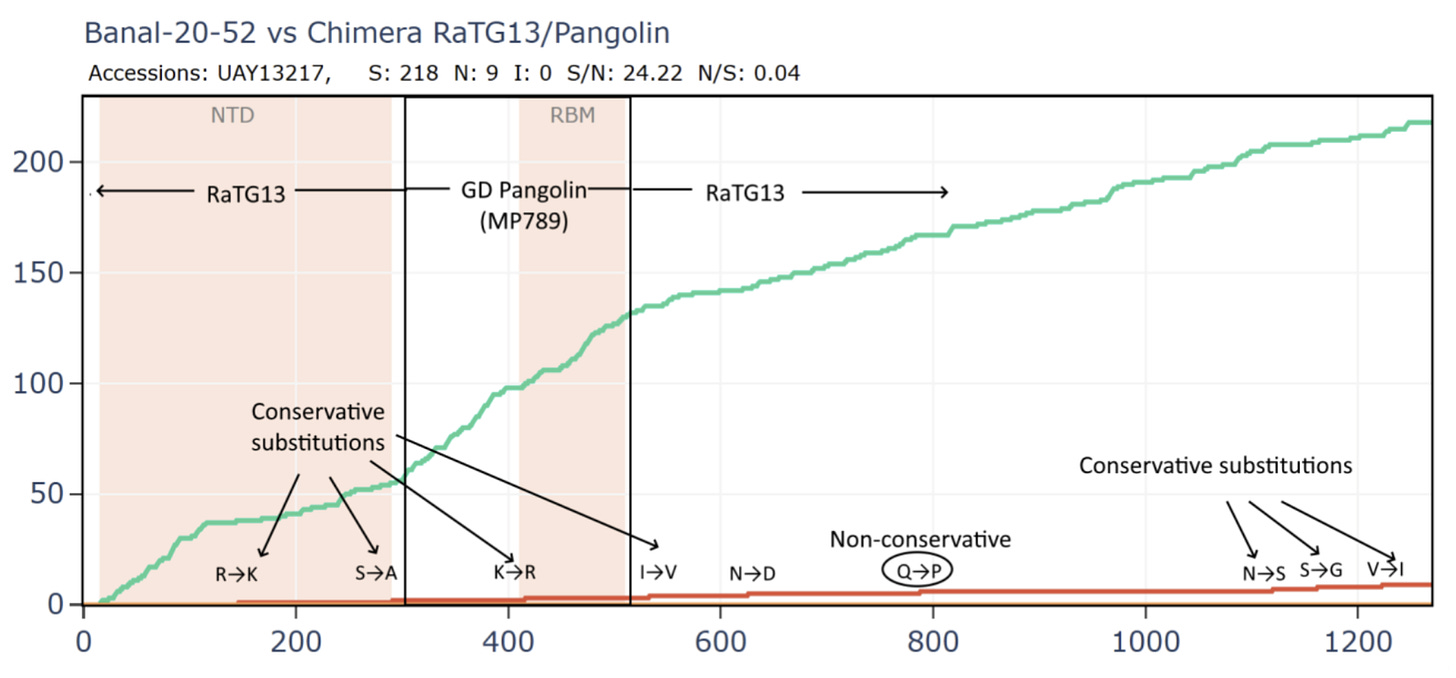

This is evolutionary nonsense. The RBM and NTD should be the most variable parts of the genome regardless of the host species, yet their evolution appears to have been all but frozen. I’m yet to receive a plausible explanation for this from biologists on the natural origin side. One attempt to explain it has it that the RBM had evolved into an optimum for binding the ACE2 variants of all 3 species (and perhaps others), therefore any mutations to it are deleterious and aren’t selected. This is evidently false. The RBMs in recent circulating human variants have over 20 amino acid mutations from the original Wuhan strain. Many of these variants are as good, if not better at binding ACE2. Bat coronaviruses also have diverse and variable RBMs. Rather than reaching a stable optimum, the RBM has been observed and modeled to accommodate mutation.

Aside from adaptation, the RBM must mutate to evade recognition by antibodies. I’ve also heard arguments that “the immune system of bats is more tolerant of pathogens, reducing selection pressure on the RBM”. I accept that the immune system of bats may be different - but it is not non-existent. Bats do produce antibodies to infection, so immune-exposed regions of viruses should mutate to evade them. This extreme reticence to evolve seems unique to a handful of recent SARS and SARS-CoV-2 related viruses. Other viruses carried by bats don’t demonstrate this lack of selection pressure.

To summarize, there are 3 reasons why the RBM and NTD should be hyper-variable in theory, and indeed usually are observed to be:

They are the most exposed to the immune system, being located at the tip of the spike, so must constantly mutate to evade recognition by antibodies.

Their protein structure is tolerant of mutation as they are comprised of flexible disordered surface loops.

Where there is a host switch: receptors often have host-specific variants, so attachment regions (particularly the RBM) should adapt for stronger binding.

If not a unique exception to laws of evolution, what could explain this?

If a nefarious actor was trying to create a false evolutionary trail to cover up an artificial pathogen, they want to show that certain features evolved naturally - but - they don’t want the sequence to be so close overall that it appeared they were in possession of the direct precursor. They need to fabricate a new sequence with some extra mutations for distance. But if they add non-synonymous mutations, they change the protein structure. This risks creating a structure that might be non-viable if someone were to attempt to synthesize it. It also might change the function of a feature they were trying to demonstrate evolved naturally. It is generally safe to add synonymous mutations which don’t change the protein encoded. Of course it would be suspicious to only add synonymous mutations, but a disproportionate number might pass unnoticed.

Banal-52 spike gene can be easily fabricated by starting from the RaTG13/PCoV sequence and adding 24 synonymous mutations for each of 9 amino acids changed. All but one of these amino acid differences are conservative substitutions in which a residue is exchanged for another with very similar properties, having only minor effect on the protein structure and function. The RaTG13 and PCoV sequences may have been fabricated in a similar way. After 5 years, we are no closer to discovering whether they are viable or can infect their putative host species (despite Ralph Baric having been approved to do this work in early 2020).

I suspect laypeople would be horrified if they knew that there is no effective way to validate sequence data. Worse, scientists almost always place blind trust in the GenBank data and incorporate it data into their studies without questioning its provenance or the reliability of the submitter. When we are breathlessly informed by the media that “scientists have discovered a new virus in bats similar to…which could cause the next pandemic”, there is no advertising of the scientists’ possible connections to the PLA’s biowarfare unit, and no disclaimer that the discovery hasn’t been independently confirmed. Peer review is often cited to assure us that work has been checked, but this misunderstands what reviewers are able and expected to do.

The reason modern progressive people like to declare that they “trust science” over faith-based belief systems is because we understand the scientific method to mean findings are independently reproducible, so verifiable. If we can’t do this ourselves because we lack expertise and resources, we assume there will be others who can - and will. In some sciences this is true. If someone claims to have invented cold fusion or a room temperature superconductor, skeptics in physics departments the world over will immediately try to debunk them.

This is not always the case in biology. In sampling pathogens from wildlife in remote areas - replication is extremely difficult to impossible. Several different groups sampled the Mojiang mine where WIV claimed to have found RaTG13, but only WIV has ever reported finding SARS-like coronaviruses. When WIV revisited the mine later they weren’t able to find it again. A massive survey of over 13,000 bats by China’s National Health Commission claimed that SARS-CoV-2 related bat viruses were no longer found in China - conveniently shifting the origin to South-East Asia.

What many assume to be science turns out to be another faith-based system, which (like religion) is open to exploitation by charlatans. It’s a safe bet that bioweaponeers aren’t of the highest integrity and are motivated and well-resourced to avoid attribution. Simply “taking their word” for it or applying a presumption of innocence is unacceptable given the dreadful toll of the pandemic, and the potential for more.

Banal-52 wasn’t the end of it. More sequences have since appeared with a very similar RBM - most of these have also been collected by or sequenced by Institut Pasteur. These will be explored in another article in very near future.

For more background on the history of French involvement with WIV and the AMMS, please see my earlier article “French complicity in the origin and cover-up of Covid”.

A great exposition. Many thanks for all your hard and insightful work. Adrian G.

This really seems like the French government owes information to the public.