Zen and the Art of Collecting Batshit

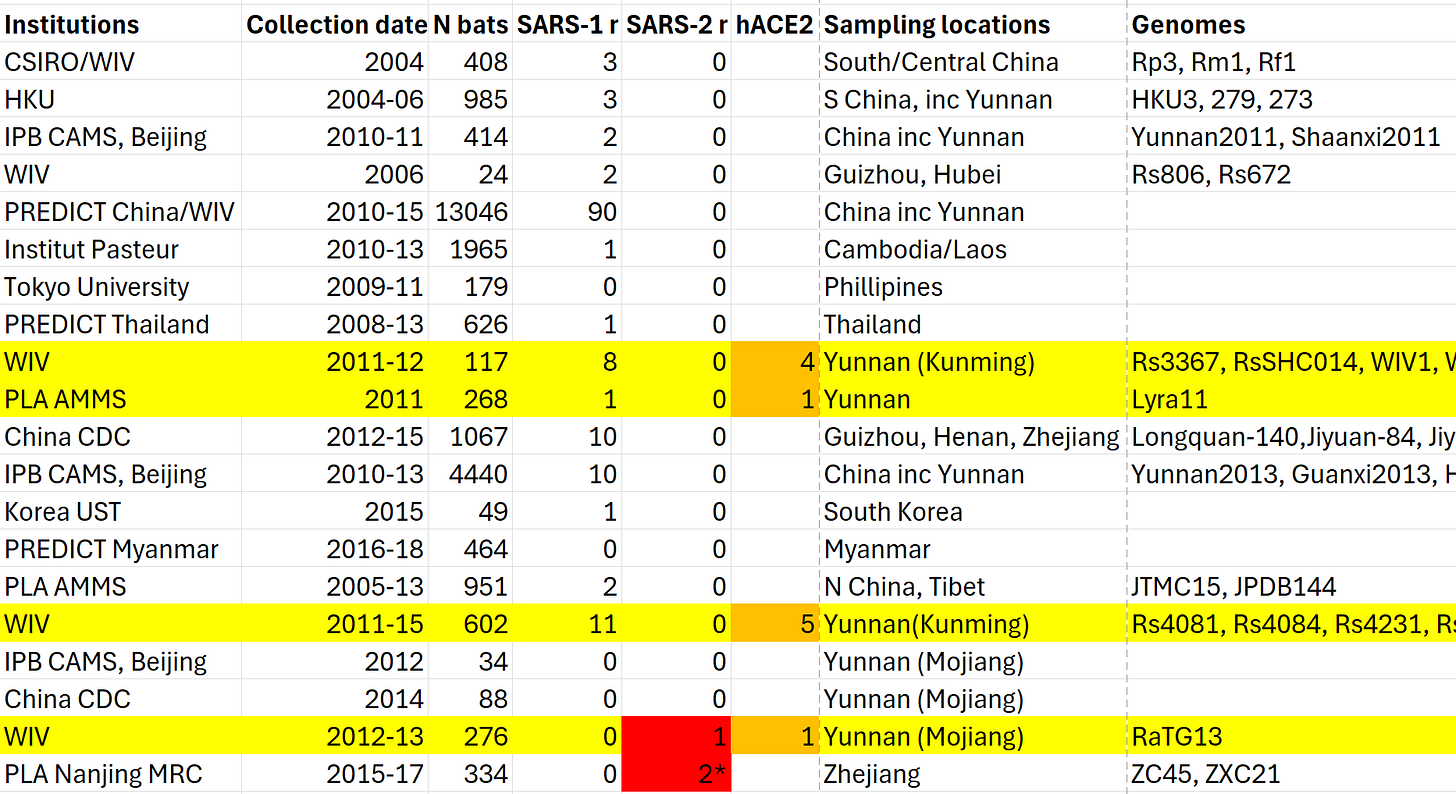

Between SARS-1 and 2, teams of scientists scoured China and South-East Asia for bat viruses which might have human pandemic potential. Only two groups found any: WIV, and the PLA.

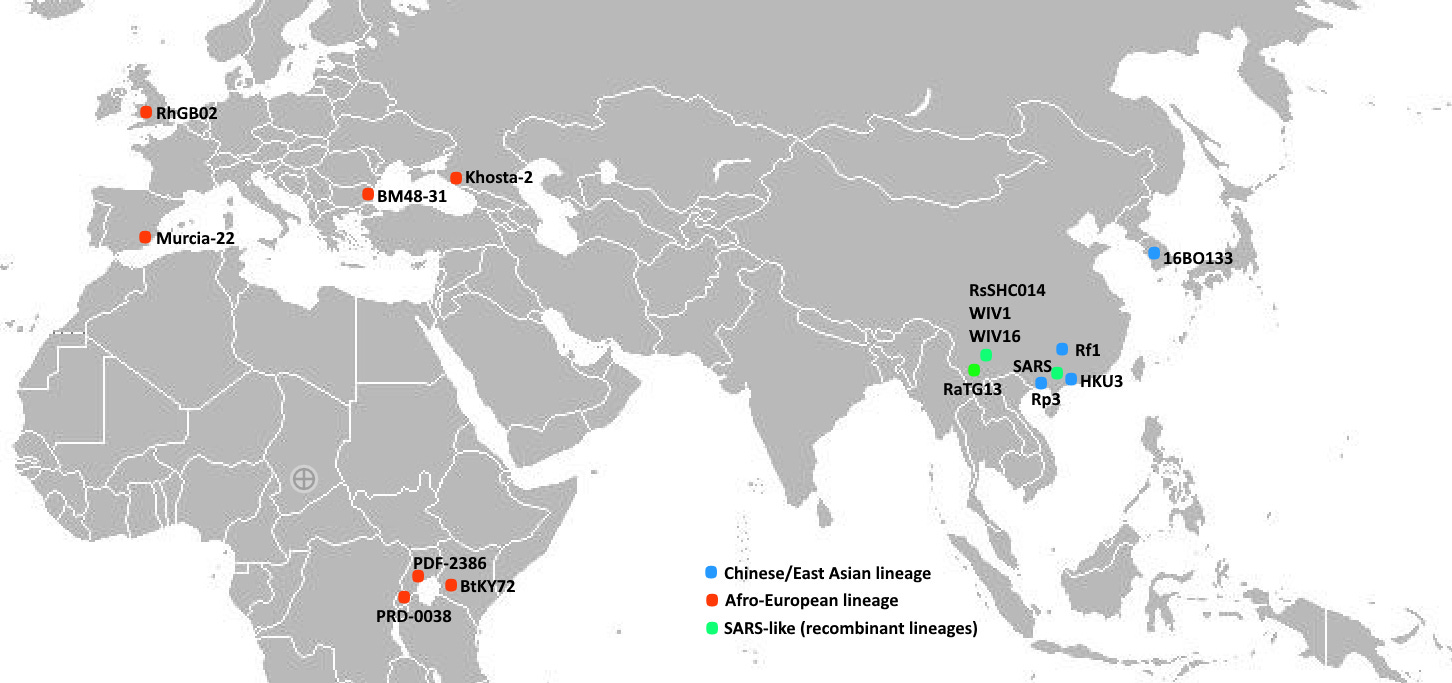

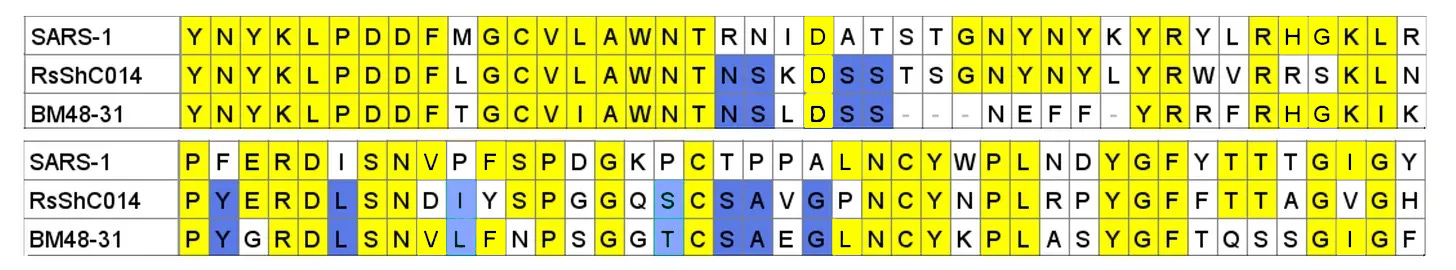

When Drosten et al sequenced a novel coronavirus from Bulgaria in 2008 it became evident that SARS was a recombinant of two bat coronavirus lineages which evolved in isolation. BM48-31 was the first member of a lineage which has now been sampled (sparsely) across a vast range in Europe and Africa. Another clade had been discovered in 2004-2006 in China, separately by a group from HKU, and a collaboration between CSIRO, EcoHealth and WIV.

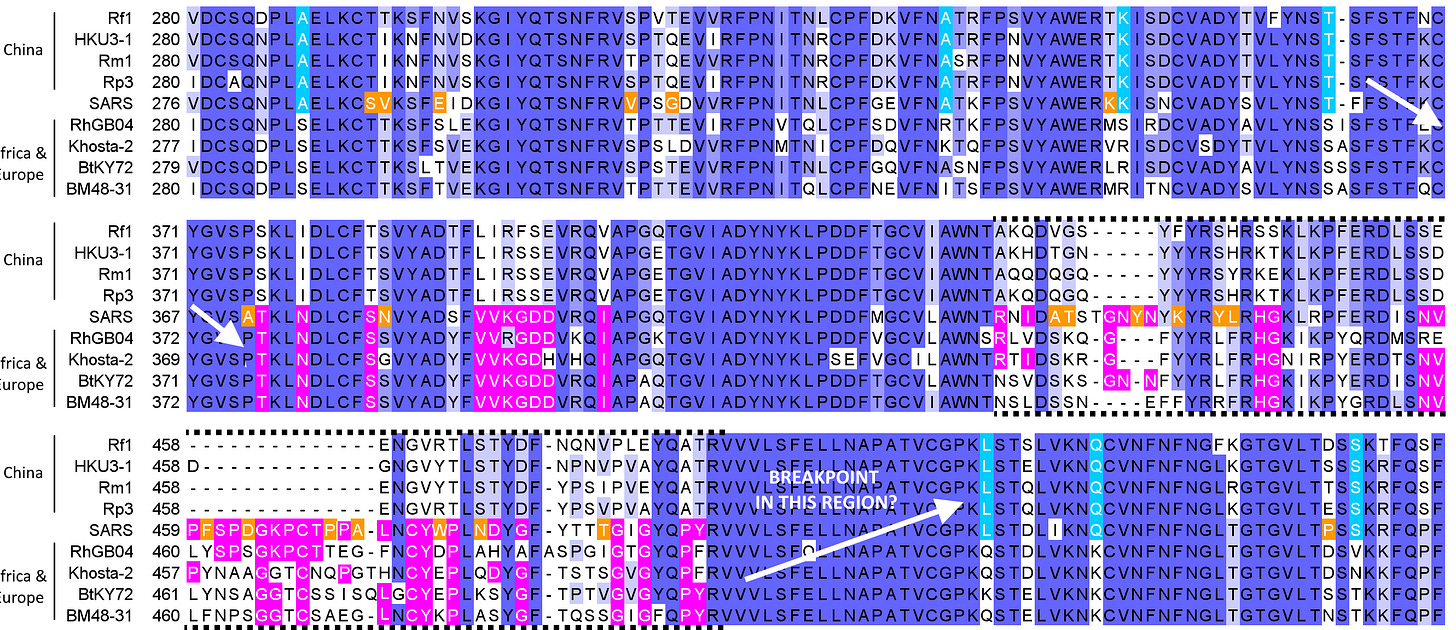

On a sequence alignment of representatives of these two lineages, SARS spike sequence seems to alternate between agreeing with the Asian clade (blue), then the Afro-European clade (pink) in the RBD then returns to following to the Asian clade (blue). There are also several residues unique to SARS (orange).

This is somewhat simplified…a more detailed discussion in a future article.

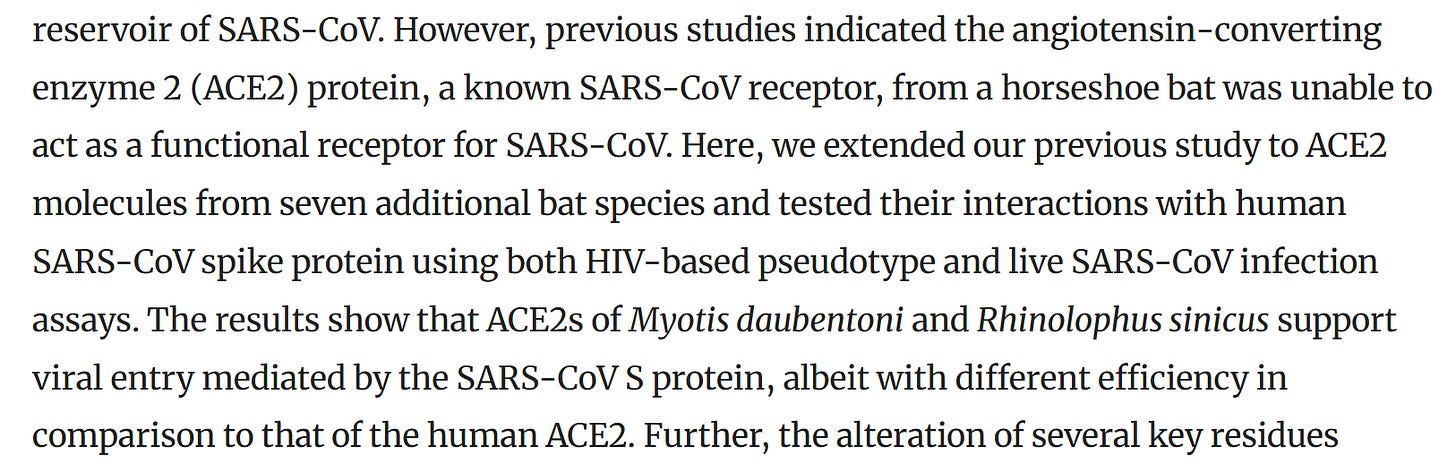

Once BM48-31 was published, it would have been possible to interpret that a recombination with another bat virus happened with breakpoints located somewhere on either side of the RBD. This RBD region has far closer resemblance to BM48-31 than the Chinese clade. Crucially, members of the Afro-European lineage have since been shown to bind ACE2 (though not as well as SARS), while the Chinese lineage cannot. This is because the Chinese lineage has many deletions, it’s RBM is shorter. The Afro-European lineage has fewer deletions, but SARS is still longer by 3-5 amino acids.

The intuition that the RBD had been acquired by recombination led WIV to experiment with chimeric spike proteins. They inserted regions of the RBD of SARS into Rp3, using various breakpoints, to determine the minimal region required to make Rp3 infectious to human cells. Ralph Baric and Marc Denison independently experimented. They went a step further than WIV, making a live clone. More about this in previous article below.

Drosten’s discovery re-ignited interest in hunting for novel bat CoVs in China. Before that the source of the RBD had remained a mystery, some had even suggested the source might be a bird or rat virus. There was still no explanation of how the RBD most similar to a bat virus from Bulgaria (some 8000km away) may have ended up in a Chinese backbone. It suggested there must be some missing link bat virus somewhere in China.

Starting in 2010, teams that included China’s central and provincial CDCs and the Institute of Pathogen Biology in Beijing (CAMS) collected thousands of bat samples across China.

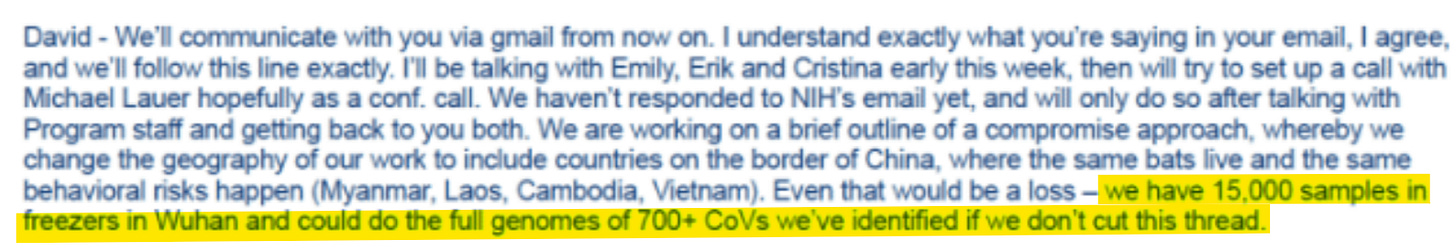

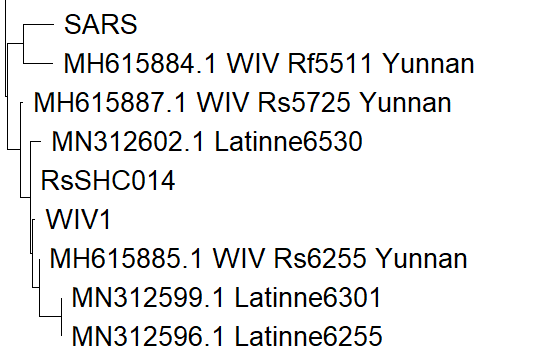

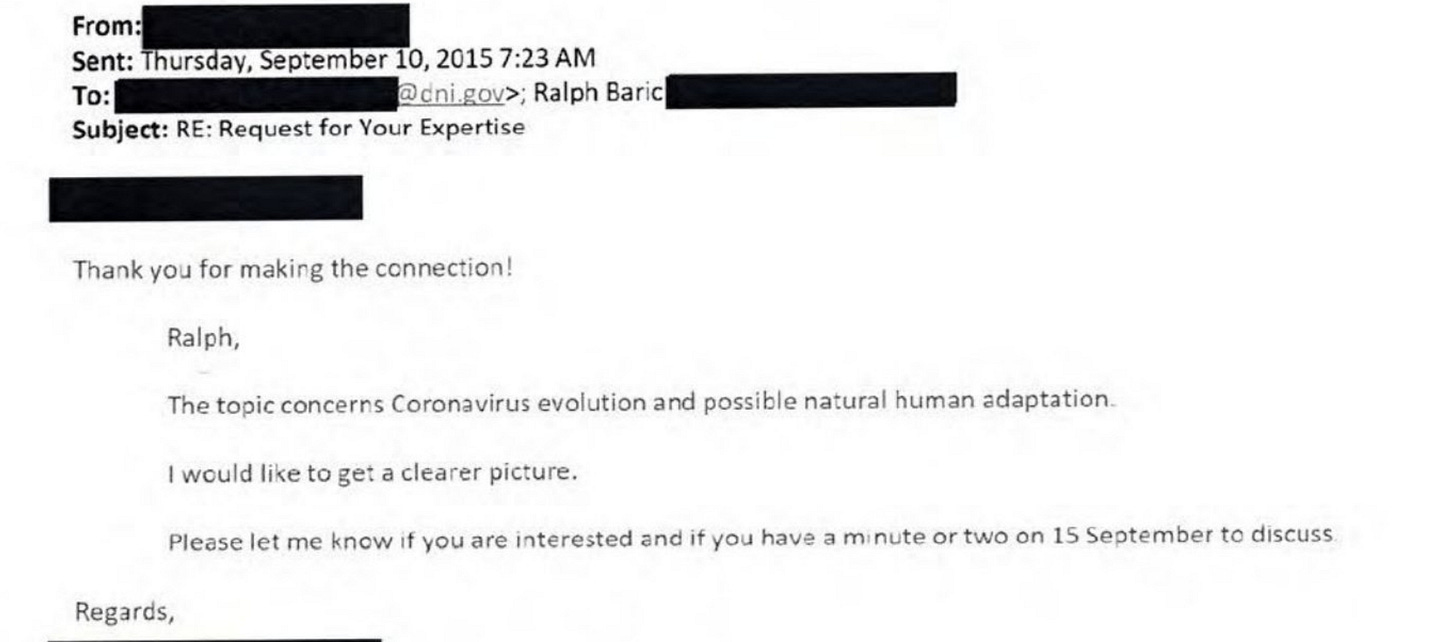

Also in 2010 (according to former EcoHealth executive Andrew Huff) Peter Daszak was approached by the CIA, who wanted to “keep an eye on things” in China. EcoHealth received funding under the PREDICT program to sample bats within China. But they didn’t work independently, much of the work was performed by WIV. Over the next 5 years the collaboration sampled over 13,000 bats. In late 2019, they published 600 novel bat coronavirus species, of which 90 are SARS related. The resulting paper (published March 2020) is referred to as Latinne et al.

It can be difficult to sequence a full genome, and at the time it was unrealistic to generate a full sequence for every virus. Usually as a first pass, a short “fingerprint” is sequenced - a partial RdRp. This can be used to identify close relatives and ancestors and position the virus in a phylogenetic tree. When evolution is as normal, this is useful for identifying samples of interest for follow-up sequencing. But evolution in sarbecovs is far from normal - if WIV’s claims are to be believed. Frequent recombination might mean separate regions like RdRp and spike are related differently, they may come from different sources.

That implies two viruses closely related by RdRp, might have different ACE2 binding capability, so the spike gene should be sequenced to properly determine this. The vast majority of sequences in Latinne et al have not had their spike sequenced. Unfortunately, the thousands of samples collected remain stored at WIV, so there’s no possibility of independently confirming the existence of any ACE2 binding spikes. But it is clear from RdRp alone that none of these viruses belong to the SARS-CoV-2 clade.

Discovery of the Magical Cave of Recombination

From a table of the many bat coronavirus surveys, it’s clear that some groups had better luck than others. Altogether over 26,000 bats were sampled across China and South-Asia. Eleven viruses with a SARS-like RBD were sequenced. All but one of these were discovered by WIV at a single site, Shitou cave near Yunnan’s capital, Kunming. The other was found by an AMMS Institute of Military Veterinary Science group led by Tu Changchun, who had been previously involved in WIV/CSIRO’s investigations into civets.

Some scientists have suggested to me that the reason no-one else managed to sequence a virus SARS-like RBD (or even a close relative) is because some viruses can be very localized, evolving in a geographically isolated bat colony. But Tu Changchun’s discovery was made 500km away, on the other side of Yunnan, in a different bat species, so they ought to be more widespread. WIV and AMMS weren’t the only groups to sample in Yunnan either - as the table above indicates.

And if the colony was truly isolated - how did RsSHC014 evolve this homology to a virus from Bulgaria - 8000k away?

Absence of evidence isn’t necessarily evidence of absence. We can’t be 100% certain similar viruses don’t exist, no matter how much sampling is done. But this violates a tenet of the scientific method - falsifiability. WIV’s claims aren’t falsifiable, so they need further corroboration. There are a handful of Latinne et al sequences that are closely related by RdRp - but that we don’t have spike sequences for. These might have been used to confirm WIV’s results, even if impossible to refute them.

But we can surely say that outside of this cave, such viruses must be very rare. How did WIV stumble upon this “rich gene pool”, what led them to Yunnan in the first place?

In 2010, a WIV/HKU collaboration announced they had discovered 2 new viruses (Rs672 and Rs806) from samples WIV collected in 2006. This paper is unusual in several ways. Firstly, they only had samples from 24 bats, yet managed to extract two complete sarbecov genomes. Other groups needed hundreds of samples for each genome sequenced. This is partly because bats infected with a similar virus are relatively rare, and because RNA breaks down rapidly in feces, often only small parts of a genome can be obtained from a single sample. But once again, WIV got lucky.

Rs672 has a 579-nucleotide deletion in sp3 - a distinguishing feature it shared only with a human patient from the late phase of SARS. The late phase occurred several months after SARS had been thought eliminated, and consisted of just four cases. Crucially, the same strain was sampled from civets at the same time. This was the key evidence in favor of civet to human spillover and led to the mass slaughter of farmed civets. Rs672 now seemed to offer a further clue linking bats to SARS. Among all viruses subsequently sequenced, this 579-nt deletion has only been found once more (coincidentally by Tu Changchun’s AMMS group).

WIV’s earliest discovery, Rp3, at the time closest to SARS “backbone” had been sampled from bat species R. pearsoni. But they had already shown R. pearsoni ACE2 was incapable of binding SARS RBD. If two viruses can’t co-infect the same host cell, recombination is impossible. So WIV announced they had previously misidentified Rp3’s host - it had actually come from R. sinicus, they now claimed. Shortly after this they announced they had discovered that R. sinicus ACE2 could bind SARS. Problem solved.

Rs672 was sampled in Guizhou province, further west from Rp3 and other discoveries. A map indicates that the same clade of R. sinicus bats inhabits Guizhou and Yunnan. This points to where they will go next, though there was no evidence of SARS-related CoVs in Yunnan at the time. WIV commenced a 12-month survey in Shitou cave apparently on a hunch. And again luck was with them, they found the viral mother lode. the cave, they claimed, contains all the genetic “building blocks” of SARS, which are frequently recombining into new mix-and-match viruses, some potentially human infectious.

Mojiang mojo

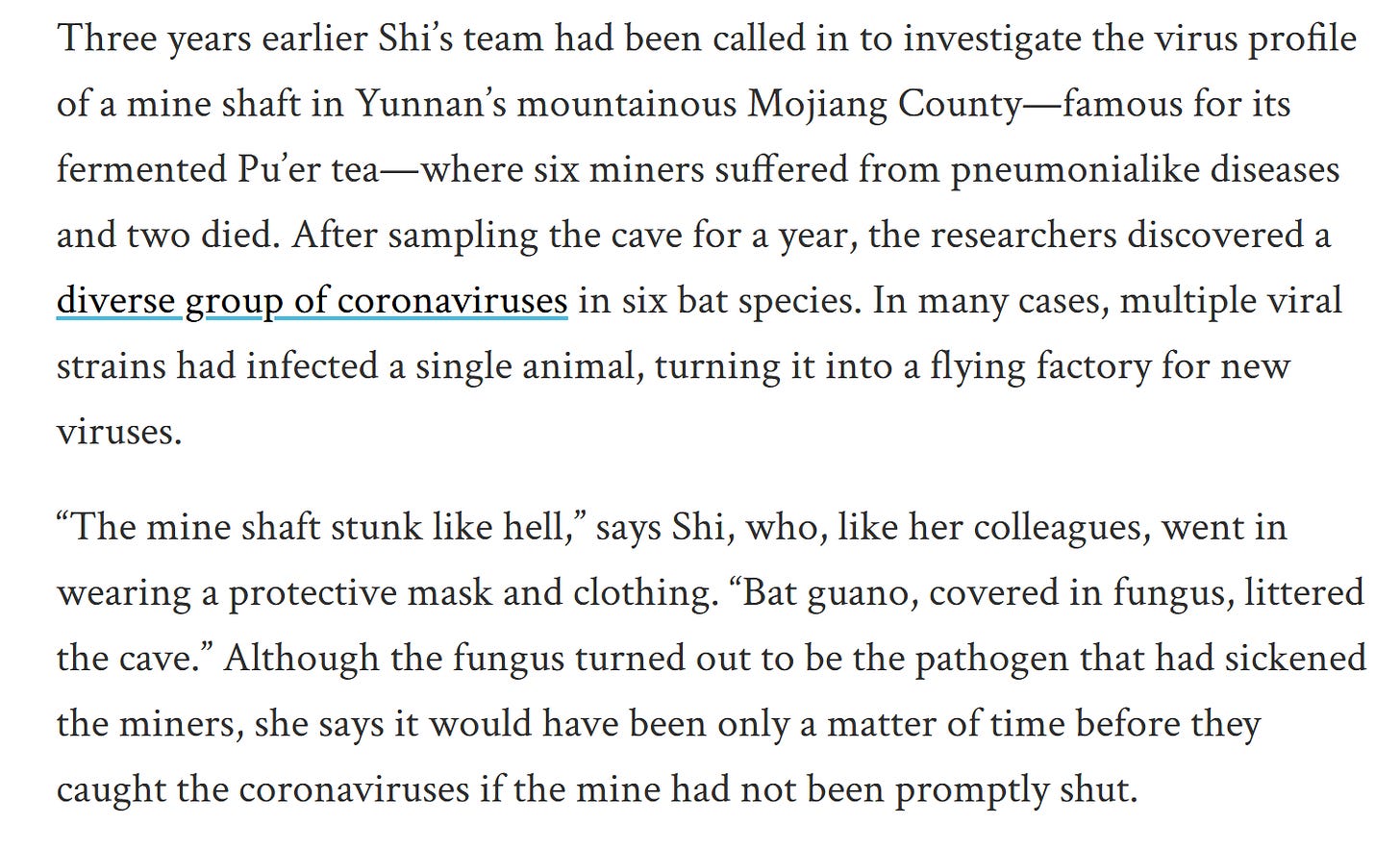

In April 2012 (according to a master’s student thesis) Kunming Hospital treated 6 artisanal miners who were apparently clearing guano from an abandoned mine-shaft when they became ill with a respiratory disease. Three eventually died. WIV were reportedly sent some of their clinical samples and at one time claimed they were positive for SARS antibodies. In an early 2020 interview, Zhengli Shi denied this, claiming they had caught a fungal disease, not a SARS-like virus.

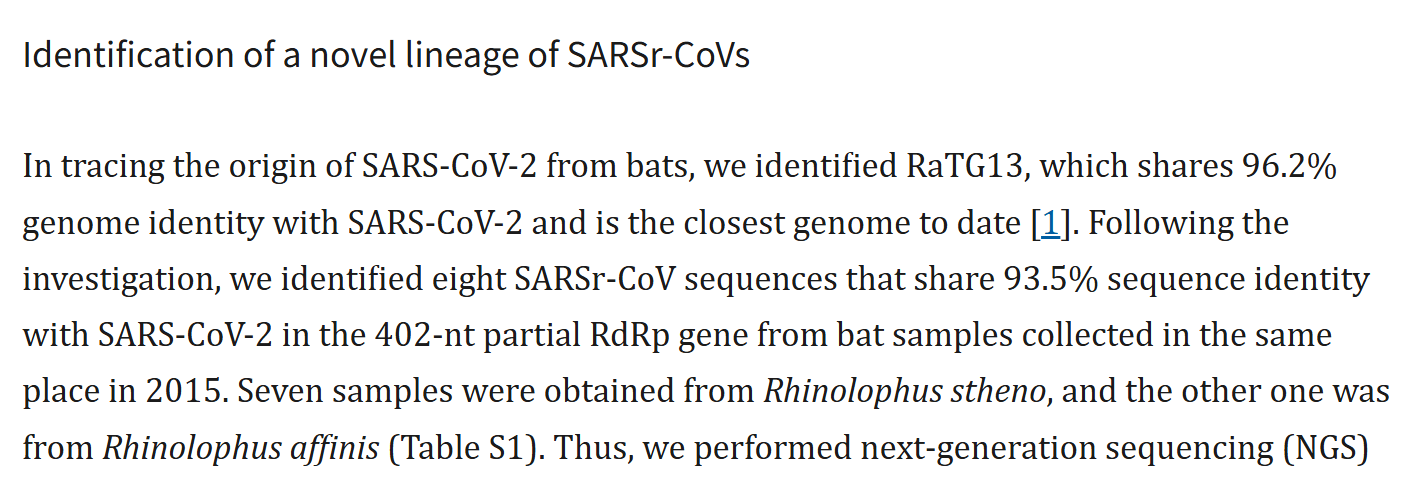

Reports of the incident sent at least 3 teams of scientists scurrying to the mine to sample. Once again WIV succeeded where groups from China CDC and the Institute of Pathogen Biology found little of interest, despite repeat visits. WIV traveled to Mojiang three times in 2012-13, and sampled 276 bats. They only reported one SARS-like virus, but it is of special importance. It would become the first member of the SARS-CoV-2 clade: RaTG13. Despite their interest in the cave, WIV claimed to have not fully sequenced RaTG13 until 2018, and it wasn’t made public until late January 2020.

Some lab-leakers have proposed that perhaps WIV found other viruses in the mine that were even closer to SARS-CoV-2. Another intriguing hypothesis is that the miners themselves became incubators for the virus that eventually became SARS-CoV-2 (possibly with some extra engineering). Prolonged infection and suppressed immune response may have given the virus time to become better adapted to the human respiratory tract.

But I suspect the incident may never even have happened. The master’s thesis is the only primary source. Its submission date is given as June, 2013, but though it contains all the known clinical detail, it isn’t cited by others. Were the claims made verbally by WIV? Basic details are stated inconsistently by secondary sources. The date of the incident is variously documented as 2011, April 2012, June 2012, and November 2012, even the number of deaths is uncertain, some sources said only 2 had died, others said 3. Importantly, the type of clinical tests WIV claimed to perform, and the results obtained are inconsistent. WIV didn’t mention the incident at all in their 2016 paper describing their sampling at the mine. More recently WIV seemed to deny the miners tests were ever SARS-positive, offering no explanation for why it attracted the interest of multiple groups.

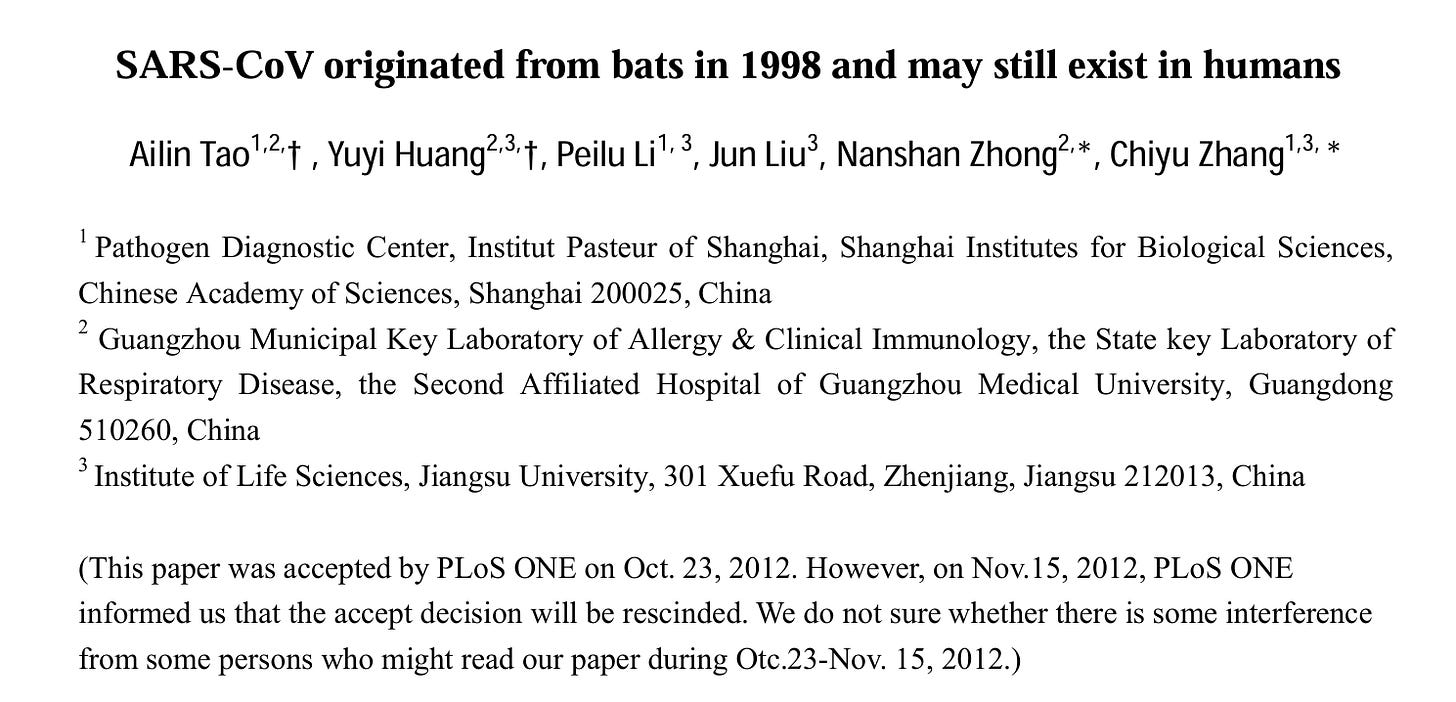

The thesis also claims that famous Guangdong doctor Zhong Nanshan, who was closely involved in all aspects of SARS: treatment, epidemiology, origin - was asked to advise on the miners’ case. Interestingly, in October 2012, Zhong had a paper accepted for publication by PLoS One, but a month later the acceptance was rescinded. The group posted their pre-print to ArXiv with a bizarre statement hinting that someone had intervened to have publication canceled.

Zhong’s pre-print proposes that SARS originated as a spillover in Guangdong, as early as 1998. It spilled directly from bats to humans, and evolved into two strains - one virulent (SARS), and one mild. Humans later infected civets with the mild strain. The authors also believed the mild strain is still circulating in Guangdong, 20% of samples of children they tested were seropositive. This is a very different origin narrative to the one WIV were proposing. Zhong’s paper doesn’t mention Yunnan at all. If Zhong had heard of the miners’ incident, he hadn’t thought it significant.

So RaTG13 - the only true SARS-CoV-2r from 26,000 bats sampled before the pandemic - was found because miners caught a fungal disease, which co-incidentally had similar symptoms to SARS? Serendipity strikes again for WIV. Zhengli Shi later said that while the miners’ disease was fungal, if the mine had stayed open any longer they would have caught a coronavirus. So there’s that.

In late 2020, WIV revealed 8 more viruses from the same mineshaft. Based on RdRp these aren’t closely related to SARS-CoV-2, but closer than the SARS-1 clade. They’re meant to be an evolutionary intermediate. WIV claim they sequenced these only after linking RaTG13 to SARS-CoV-2 in 2020.

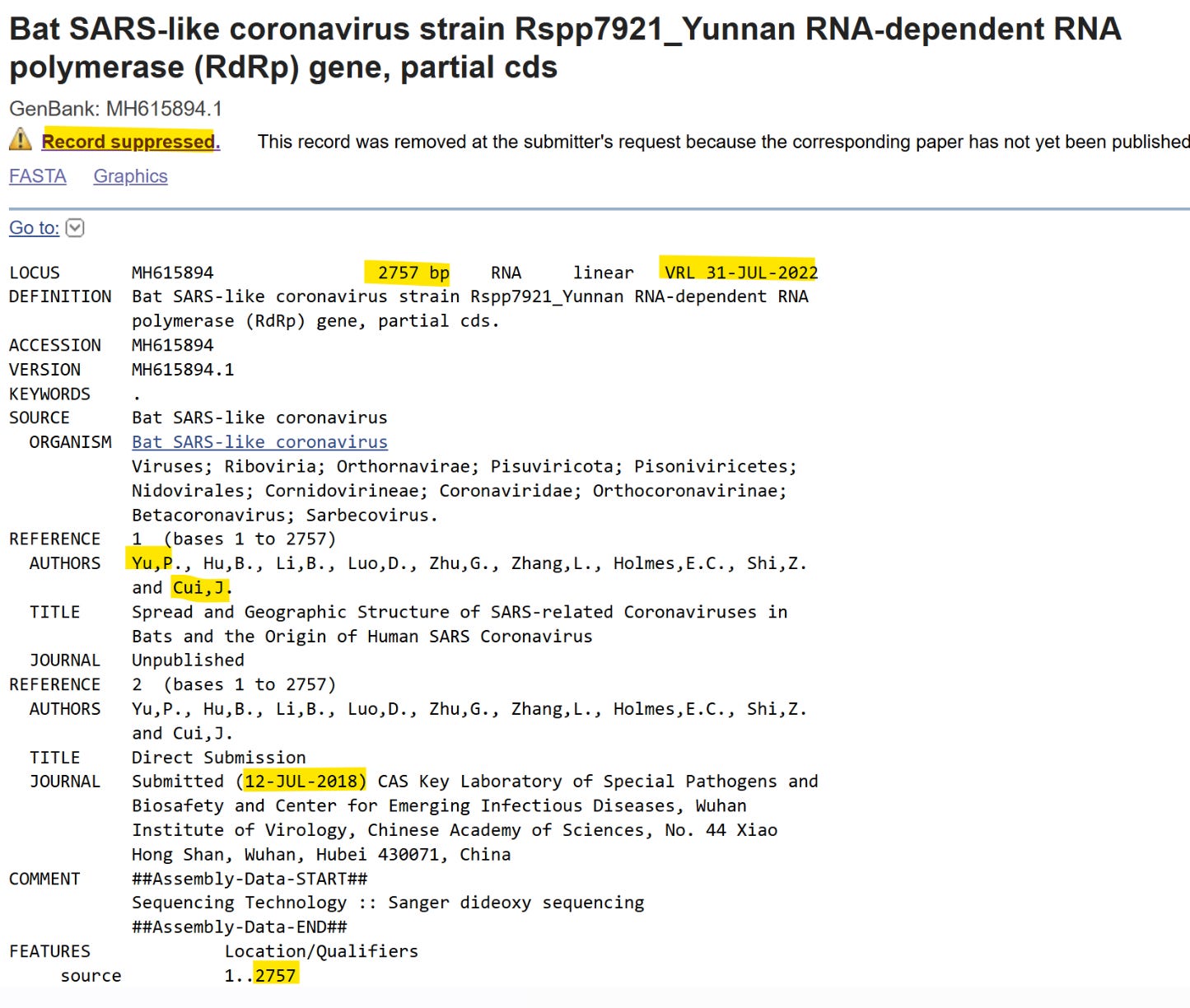

This is false, and not an innocent mistake. The thesis of WIV student Yu Ping completed a year earlier (obtained by Drastic) utilized the full 2757-nt RdRp sequence. What’s more the full spike, RdRp and ORF8 sequences of these viruses had been uploaded to GenBank in July 2018 - but they remained “suppressed”, hidden from public sight. They were briefly exposed to public view when an automatic embargo they had set expired, and quickly returned to “suppressed” mode at WIV’s request.

As with RaTG13, Yu Ping, and supervisor Jie Cui were again left off the author list when the paper was published in August 2021. Cui had by then transferred to Institut Pasteur Shanghai. Although sampled in 2015, these sequences weren’t provided to EcoHealth/PREDICT. Clearly some sequences WIV decided to keep to themselves. Do they even represent real viruses, or were they fabricated to support a phony natural origin?

My view is that there are no bat coronaviruses with human pandemic potential in nature. The myth of the Mojiang miners was confected to suggest that spillovers from bats to humans had already occurred from a virus similar to - but not - RaTG13. A persistent infection starting in the lungs might plausibly result in a bat virus gaining human respiratory tropism. This backfired when WIV and RaTG13 became the focus of lab-origin allegations.

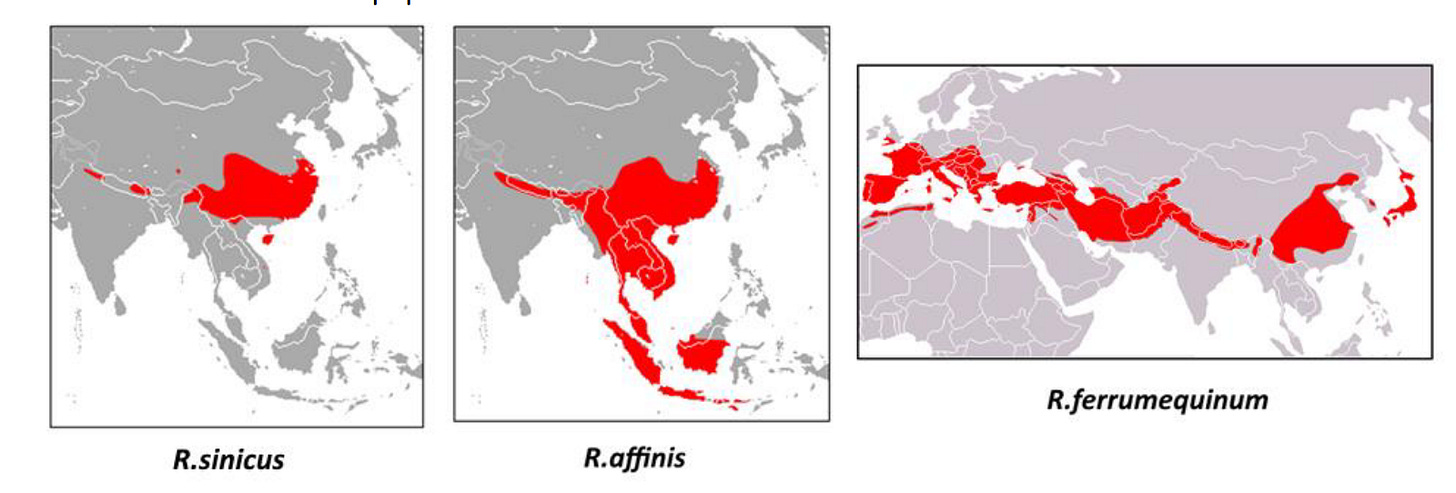

Though unlikely, a virus similar to RaTG13 might hypothetically be transformed into SARS-CoV-2 by recombining with a coronavirus purportedly found in Manis javanica - the Malayan pangolin. M. javanica doesn’t inhabit Yunnan, so this detail was likely intended to point to an origin outside China’s borders. The choice of bat host also seems intentional. R. affinis’ range extends deep into South-East Asia unlike R. sinicus, which is largely confined to China. Before RaTG13, WIV had made no discoveries in R. affinis. There was only Tu Changchun’s LyRa11.

This left the question of how did a SARS-like RBD travel from Europe to Yunnan, given that neither R. sinicus, or R. affinis are found anywhere close to Europe or Africa. Once again Tu Changchun came to the rescue. In 2016 he claimed to have sampled JTMC15 (the 3rd virus with the 579nt deletion) in R. ferrumequinum. A larger bat, its range extends from Japan to the UK.

The provenance of pangolin coronaviruses is also murky. The AMMS are intimately involved in their discovery (or invention), claiming to have first isolated one in 2017. They were unknown by others until they appeared in a low-key paper in September 2019. But even then, their sequence data was unpublished until WIV simultaneously released the RaTG13 sequence around 22nd January, 2020. Later in 2020, EcoHealth analyzed samples from 334 pangolins collected between 2009 and 2019, and detected no coronaviruses. Another example of the different fortunes of virus hunters.

Simon Wain-Hobson recently brought up the fact that there's an order of magnitude more SAR1-like sequences than SARS2 like ones. I actually hadn't really grokked that there were hundreds of the former.

He seemed to favor the explanation that the samples and sequences might exist, but people won't publish them because of what might be inferred from that data.

I dunno. That explanation doesn't seem to fit with the table you have above.

Just a bioinformatic note on Yu2018

The original ORF8 experiments were loaded in 2018…

https://web.archive.org/web/20220809085043/https:/www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=Spread+and+Geographic+Structure+of+SARS-related+Coronaviruses+in+++++++++++++Bats+and+the+Origin+of+Human+SARS+Coronavirus

But the rest were loaded when the original paper was changed from an immune evading ORF8 based experiment on SARSr data to an evolutionary paper…the bioinformatics are very exact here 25-OCT-2019 was when this data was loaded.

The rest is propaganda…including the paper we are not allowed to read.

https://web.archive.org/web/20230308013429/https://twitter.com/EdwardCHolmes

And the self refuting denials

https://theconversation.com/how-conspiracy-theories-about-covids-origins-are-hampering-our-ability-to-prevent-the-next-pandemic-261475

This all means that CSIRO and USyd have more details to share…

https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698&type=printable